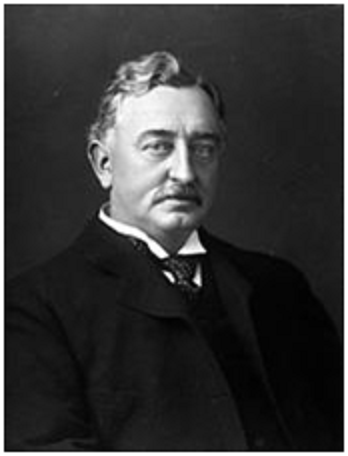

History - Cecil John Rhodes (CJR)

Cecil John Rhodes PC (5 July 1853 – 26 March 1902) was a British

businessman, mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served

as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896. An ardent

believer in British imperialism, Rhodes and his British South Africa

Company founded the southern African territory of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe

and Zambia), which the company named after him in 1895. South Africa's

Rhodes University is also named after him. Rhodes set up the provisions

of the Rhodes Scholarship, which is funded by his estate, and put much

effort towards his vision of a Cape to Cairo Railway through British

territory.

The son of a vicar, Rhodes grew up in Bishop's Stortford, Hertfordshire,

and was a sickly child. He was sent to South Africa by his family when

he was 17 years old in the hope that the climate might improve his

health. He entered the diamond trade at Kimberley in 1871, when he was

18, and over the next two decades gained near-complete domination of the

world diamond market. His De Beers diamond company, formed in 1888,

retains its prominence into the 21st century.

Rhodes entered the Cape Parliament in 1880, and a decade later became

Prime Minister. After overseeing the formation of Rhodesia during the

early 1890s, he was forced to resign as Prime Minister in 1896 after the

disastrous Jameson Raid, an unauthorised attack on Paul Kruger's South

African Republic (or Transvaal).

One of Rhodes's primary motivators in politics and business was his

professed belief that the Anglo-Saxon race was, to quote his will, "the

first race in the world". Under the reasoning that "the more of the

world we inhabit the better it is for the human race", he advocated

vigorous settler colonialism and ultimately a reformation of the British

Empire so that each component would be self-governing and represented in

a single parliament in London. Ambitions such as these, juxtaposed with

his policies regarding indigenous Africans in the Cape Colony—describing

the country's black population as largely "in a state of barbarism", he

advocated their governance as a "subject race", and was at the centre of

moves to marginalise them politically—have led recent critics to

characterise him as a white supremacist and "an architect of apartheid".

Historian Richard A. McFarlane has called Rhodes "as integral a

participant in southern African and British imperial history as George

Washington or Abraham Lincoln are in their respective eras in United

States history."

After Rhodes's death in 1902, at the age of 48, he was buried in the

Matopos Hills in what is now Zimbabwe.

Education

A portrait bust of Rhodes on the first floor of No. 6 King Edward Street

marks the place of his residence whilst in Oxford.

In 1873, Rhodes left his farm field in the care of his business partner,

Rudd, and sailed for England to study at university. He was admitted to

Oriel College, Oxford, but stayed for only one term in 1873. He returned

to South Africa and did not return for his second term at Oxford until

1876. He was greatly influenced by John Ruskin's inaugural lecture at

Oxford, which reinforced his own attachment to the cause of British

imperialism.

Among his Oxford associates were James Rochfort Maguire, later a fellow

of All Souls College and a director of the British South Africa Company,

and Charles Metcalfe. Due to his university career, Rhodes admired the

Oxford "system". Eventually he was inspired to develop his scholarship

scheme: "Wherever you turn your eye—except in science—an Oxford man is

at the top of the tree".

While attending Oriel College, Rhodes became a Freemason in the Apollo

University Lodge. Although initially he did not approve of the

organisation, he continued to be a South African Freemason until his

death in 1902. The shortcomings of the Freemasons, in his opinion, later

caused him to envisage his own secret society with the goal of bringing

the entire world under British rule. According to Carroll Quigley, he

set up the Round Table movement to this end.

Politics in South Africa

In 1880, Rhodes prepared to enter public life at the Cape. With the

earlier incorporation of Griqualand West into the Cape Colony under the

Molteno Ministry in 1877, the area had obtained six seats in the Cape

House of Assembly. Rhodes chose the rural and predominately Boer

constituency of Barkly West, which would remain faithful to Rhodes until

his death.

When Rhodes became a member of the Cape Parliament, the chief goal of

the assembly was to help decide the future of Basutoland. The ministry

of Sir Gordon Sprigg was trying to restore order after the 1880

rebellion known as the Gun War. The Sprigg ministry had precipitated the

revolt by applying its policy of disarming all native Africans to those

of the Basotho nation.

In 1890, Rhodes became Prime Minister of the Cape Colony. He introduced

the Glen Grey Act to push black people from their lands and make way for

industrial development. Rhodes's view was that black people needed to be

driven off their land to "stimulate them to labour" and to change their

habits. "It must be brought home to them", Rhodes said, "that in future

nine-tenths of them will have to spend their lives in manual labour, and

the sooner that is brought home to them the better."

The growing number of enfranchised black people in the Cape led him to

raise the franchise requirements in 1892 to counter this preponderance,

with drastic effects on the traditional Cape Qualified Franchise. By

simultaneously limiting the amount of land black Africans were legally

allowed to hold while tripling the property qualifications required to

vote, Rhodes succeeded in disenfranchising the black population, as, to

quote Richard Dowden, most would now "find it almost impossible to get

back on the list because of the legal limit on the amount of land they

could hold". In addition, Rhodes was an early architect of the Natives

Land Act, 1913, which would limit the areas of the country that black

Africans were allowed to less than 10%. At the time, Rhodes would argue

that "the native is to be treated as a child and denied the franchise.

We must adopt a system of despotism, such as works in India, in our

relations with the barbarism of South Africa."

Rhodes also introduced educational reform to the area. His policies were

instrumental in the development of British imperial policies in South

Africa, such as the Hut tax.

Rhodes did not, however, have direct political power over the

independent Boer Republic of the Transvaal. He often disagreed with the

Transvaal government's policies, which he considered unsupportive of

mine-owners' interests. In 1895, believing he could use his influence to

overthrow the Boer government, Rhodes supported the infamous Jameson

Raid, an attack on the Transvaal with the tacit approval of Secretary of

State for the Colonies Joseph Chamberlain. The raid was a catastrophic

failure. It forced Cecil Rhodes to resign as Prime Minister of the Cape

Colony, sent his oldest brother Col. Frank Rhodes to jail in Transvaal

convicted of high treason and nearly sentenced to death, and contributed

to the outbreak of the Second Boer War.

In 1899, he was sued by a man named Burrows for falsely representing the

purpose of the raid and therefore convincing him to participate in the

raid, wherein he lost a leg. His suit for £3000 in damages was

successful.

Expanding the British Empire

"The Rhodes Colossus" – cartoon by Edward Linley Sambourne, published in

Punch after Rhodes announced plans for a telegraph line from Cape Town

to Cairo in 1892.

Rhodes used his wealth and that of his business partner Alfred Beit and

other investors to pursue his dream of creating a British Empire in new

territories to the north by obtaining mineral concessions from the most

powerful indigenous chiefs. Rhodes' competitive advantage over other

mineral prospecting companies was his combination of wealth and astute

political instincts, also called the 'imperial factor', as he often

collaborated with the British Government. He befriended its local

representatives, the British Commissioners, and through them organised

British protectorates over the mineral concession areas via separate but

related treaties. In this way he obtained both legality and security for

mining operations. He could then attract more investors. Imperial

expansion and capital investment went hand in hand.

The imperial factor was a double-edged sword: Rhodes did not want the

bureaucrats of the Colonial Office in London to interfere in the Empire

in Africa. He wanted British settlers and local politicians and

governors to run it. This put him on a collision course with many in

Britain, as well as with British missionaries, who favoured what they

saw as the more ethical direct rule from London. Rhodes prevailed

because he would pay the cost of administering the territories to the

north of South Africa against his future mining profits. The Colonial

Office did not have enough funding for this. Rhodes promoted his

business interests as in the strategic interest of Britain: preventing

the Portuguese, the Germans or the Boers from moving into south-central

Africa. Rhodes's companies and agents cemented these advantages by

obtaining many mining concessions, as exemplified by the Rudd and

Lochner Concessions.

Treaties, concessions and charters

Rhodes had already tried and failed to get a mining concession from

Lobengula, king of the Ndebele of Matabeleland. In 1888 he tried again.

He sent John Moffat, son of the missionary Robert Moffat, who was

trusted by Lobengula, to persuade the latter to sign a treaty of

friendship with Britain, and to look favourably on Rhodes's proposals.

His associate Charles Rudd, together with Francis Thompson and Rochfort

Maguire, assured Lobengula that no more than ten white men would mine in

Matabeleland. This limitation was left out of the document, known as the

Rudd Concession, which Lobengula signed. Furthermore, it stated that the

mining companies could do anything necessary to their operations. When

Lobengula discovered later the true effects of the concession, he tried

to renounce it, but the British Government ignored him.

During the Company's early days, Rhodes and his associates set

themselves up to make millions (hundreds of millions in current pounds)

over the coming years through what has been described as a "suppressio

veri ... which must be regarded as one of Rhodes's least creditable

actions". Contrary to what the British government and the public had

been allowed to think, the Rudd Concession was not vested in the British

South Africa Company, but in a short-lived ancillary concern of Rhodes,

Rudd and a few others called the Central Search Association, which was

quietly formed in London in 1889. This entity renamed itself the United

Concessions Company in 1890, and soon after sold the Rudd Concession to

the Chartered Company for 1,000,000 shares. When Colonial Office

functionaries discovered this chicanery in 1891, they advised Secretary

of State for the Colonies Knutsford to consider revoking the concession,

but no action was taken.

Armed with the Rudd Concession, in 1889 Rhodes obtained a charter from

the British Government for his British South Africa Company (BSAC) to

rule, police, and make new treaties and concessions from the Limpopo

River to the great lakes of Central Africa. He obtained further

concessions and treaties north of the Zambezi, such as those in

Barotseland (the Lochner Concession with King Lewanika in 1890, which

was similar to the Rudd Concession); and in the Lake Mweru area (Alfred

Sharpe's 1890 Kazembe concession). Rhodes also sent Sharpe to get a

concession over mineral-rich Katanga, but met his match in ruthlessness:

when Sharpe was rebuffed by its ruler Msiri, King Leopold II of Belgium

obtained a concession over Msiri's dead body for his Congo Free State.

Rhodes also wanted Bechuanaland Protectorate (now Botswana) incorporated

in the BSAC charter. But three Tswana kings, including KhamaIII,

travelled to Britain and won over British public opinion for it to

remain governed by the British Colonial Office in London. Rhodes

commented: "It is humiliating to be utterly beaten by these niggers."

The British Colonial Office also decided to administer British Central

Africa (Nyasaland, today's Malawi) owing tothe activism of Scots

missionaries trying to end the slave trade. Rhodes paid much of the cost

so that the British Central Africa Commissioner Sir Harry Johnston, and

his successor Alfred Sharpe, would assist with security for Rhodes in

the BSAC's north-eastern territories. Johnston shared Rhodes's

expansionist views, but he and his successors were not as pro-settler as

Rhodes, and disagreed on dealings with Africans.

Rhodesia

Rhodes and the Ndebele izinDuna make peace in the Matopos Hills, as

depicted by Robert Baden-Powell, 1896

The BSAC had its own police force, the British South Africa Police,

which was used to control Matabeleland and Mashonaland, in present-day

Zimbabwe. The company had hoped to start a "new Rand" from the ancient

gold mines of the Shona. Because the gold deposits were on a much

smaller scale, many of the white settlers who accompanied the BSAC to

Mashonaland became farmers rather than miners.

When the Ndebele and the Shona—the two main, but rival,

peoples—separately rebelled against the coming of the European settlers,

the BSAC defeated them in the First Matabele War and Second Matabele

War. Shortly after learning of the assassination of the Ndebele

spiritual leader, Mlimo, by the American scout Frederick Russell

Burnham, Rhodes walked unarmed into the Ndebele stronghold in Matobo

Hills. He persuaded the Impi to lay down their arms, thus ending the

Second Matabele War.

By the end of 1894, the territories over which the BSAC had concessions

or treaties, collectively called "Zambesia" after the Zambezi River

flowing through the middle, comprised an area of 1,143,000 km between

the Limpopo River and Lake Tanganyika. In May 1895, its name was

officially changed to "Rhodesia", reflecting Rhodes's popularity among

settlers who had been using the name informally since 1891. The

designation Southern Rhodesia was officially adopted in 1898 for the

part south of the Zambezi, which later became Zimbabwe; and the

designations North-Western and North-Eastern Rhodesia were used from

1895 for the territory which later became Northern Rhodesia, then

Zambia.

Rhodes decreed in his will that he was to be buried in Matobo Hills.

After his death in the Cape in 1902, his body was transported by train

to Bulawayo. His burial was attended by Ndebele chiefs, who asked that

the firing party should not discharge their rifles as this would disturb

the spirits. Then, for the first time, they gave a white man the

Matabele royal salute, Bayete. Rhodes is buried alongside Leander Starr

Jameson and 34 British soldiers killed in the Shangani Patrol. Despite

occasional efforts to return his body to the United Kingdom, his grave

remains there still, "part and parcel of the history of Zimbabwe" and

attracts thousands of visitors each year.

"Cape to Cairo Red Line"

One of Rhodes's dreams (and the dream of many other members of the

British Empire) was for a "red line" on the map from the Cape to Cairo

(on geo-political maps, British dominions were always denoted in red or

pink). Rhodes had been instrumental in securing southern African states

for the Empire. He and others felt the best way to "unify the

possessions, facilitate governance, enable the military to move quickly

to hot spots or conduct war, help settlement, and foster trade" would be

to build the "Cape to Cairo Railway".

This enterprise was not without its problems. France had a rival

strategy in the late 1890s to link its colonies from west to east across

the continent and the Portuguese produced the "Pink Map", representing

their claims to sovereignty in Africa. Ultimately, Belgium and Germany

proved to be the main obstacles to the British dream until the United

Kingdom seized Tanganyika from the Germans as a League of Nations

mandate.

Political views

Rhodes wanted to expand the British Empire because he believed that the

Anglo-Saxon race was destined to greatness. In his last will and

testament, Rhodes said of the English, "I contend that we are the first

race in the world, and that the more of the world we inhabit the better

it is for the human race. I contend that every acre added to our

territory means the birth of more of the English race who otherwise

would not be brought into existence."

Rhodes wanted to make the British Empire a superpower in which all of

the British-dominated countries in the empire, including Canada,

Australia, New Zealand, and Cape Colony, would be represented in the

British Parliament. Rhodes included American students as eligible for

the Rhodes scholarships. He said that he wanted to breed an American

elite of philosopher-kings who would have the United States rejoin the

British Empire. As Rhodes also respected and admired the Germans and

their Kaiser, he allowed German students to be included in the Rhodes

scholarships. He believed that eventually the United Kingdom (including

Ireland), the US, and Germany together would dominate the world and

ensure perpetual peace.

Rhodes's views on race have been debated. Critics have labelled him as

an "architect of apartheid" and a "white supremacist", particularly

since 2015. According to Magubane, Rhodes was "unhappy that in many Cape

Constituencies, Africans could be decisive if more of them exercised

this right to vote under current law," with Rhodes arguing that "the

native is to be treated as a child and denied the franchise. We must

adopt a system of despotism, such as works in India, in our relations

with the barbarism of South Africa". Rhodes advocated the governance of

indigenous Africans living in the Cape Colony "in a state of barbarism

and communal tenure" as "a subject race. I do not go so far as the

member for Victoria West, who would not give the black man a vote. ...

If the whites maintain their position as the supreme race, the day may

come when we shall be thankful that we have the natives with us in their

proper position."

However historian Raymond C. Mensing, notes that Rhodes has the

reputation as the most flamboyant exemplar of the British imperial

spirit, and always believed that British institutions were the best.

Mensing argues that Rhodes quietly developed a more nuanced concept of

imperial federation in Africa and that his mature views were more

balanced and realistic. According to Mensing 1986, pp. 99–106, Rhodes

was not a biological or maximal racist and despite his support for what

became the basis for the apartheid system, he is best seen as a cultural

or minimal racist.

On domestic politics within Britain, Rhodes was a supporter of the

Liberal Party. Rhodes's only major impact was his large-scale support of

the Irish nationalist party, led by Charles Stewart Parnell (1846–1891).

Rhodes worked well with the Afrikaners in the Cape Colony. He supported

teaching Dutch as well as English in public schools. While Prime

Minister of the Cape Colony, he helped to remove most of their legal

disabilities. He was a friend of Jan Hofmeyr, leader of the Afrikaner

Bond, and it was largely because of Afrikaner support that he became

Prime Minister of the Cape Colony. Rhodes advocated greater

self-government for the Cape Colony, in line with his preference for the

empire to be controlled by local settlers and politicians rather than by

London.

Oxbridge scholar and Zimbabwean author Peter Godwin, whilst critical of

Rhodes, writes that he needs to be viewed via the prisms and cultural

and social perspective of his epoch, positing that Rhodes "was no

19th-century Hitler. He wasn't so much a freak as a man of his

time...Rhodes and the white pioneers in southern Africa did behave

despicably by today's standards, but no worse than the white settlers in

North America, South America, and Australia; and in some senses better,

considering that the genocide of natives in Africa was less complete.

For all the former African colonies are now ruled by indigenous peoples,

unlike the Americas and the Antipodes, most of whose aboriginal natives

were all but exterminated."

Godwin goes on to say "Rhodes and his cronies fit in perfectly with

their surroundings and conformed to the morality (or lack of it) of the

day. As is so often the case, history simply followed the gravitational

pull of superior firepower."

Personal life

Rhodes never married, pleading, "I have too much work on my hands" and

saying that he would not be a dutiful husband.

Princess Radziwiłł

In the last years of his life, Rhodes was stalked by Polish princess

Catherine Radziwiłł, born Rzewuska, who had married into the noble

Polish family Radziwiłł. The princess falsely claimed that she was

engaged to Rhodes, and that they were having an affair. She asked him to

marry her, but Rhodes refused. In reaction, she accused him of loan

fraud. He had to go to trial and testify against her accusation. She

wrote a biography of Rhodes called Cecil Rhodes: Man and Empire Maker.

Her accusations were eventually proven to be false.

Second Boer War

French caricature of Rhodes, showing him trapped in Kimberley during the

Second Boer War, seen emerging from tower clutching papers with

champagne bottle behind his collar.

During the Second Boer War Rhodes went to Kimberley at the onset of the

siege, in a calculated move to raise the political stakes on the

government to dedicate resources to the defence of the city. The

military felt he was more of a liability than an asset and found him

intolerable. The officer commanding the garrison of Kimberley,

Lieutenant Colonel Robert Kekewich, experienced serious personal

difficulties with Rhodes because of the latters' inability to

co-operate;

Despite these differences, Rhodes's company was instrumental in the

defence of the city, providing water, refrigeration facilities,

constructing fortifications, manufacturing an armoured train, shells and

a one-off gun named Long Cecil.

Rhodes used his position and influence to lobby the British government

to relieve the siege of Kimberley, claiming in the press that the

situation in the city was desperate. The military wanted to assemble a

large force to take the Boer cities of Bloemfontein and Pretoria, but

they were compelled to change their plans and send three separate

smaller forces to relieve the sieges of Kimberley, Mafeking and

Ladysmith.

Death and legacy

Although Rhodes remained a leading figure in the politics of southern

Africa, especially during the Second Boer War, he was dogged by ill

health throughout his relatively short life.

He was sent to Natal aged 16 because it was believed the climate might

help problems with his heart. On returning to England in 1872 his health

again deteriorated with heart and lung problems, to the extent that his

doctor, Sir Morell Mackenzie, believed he would only survive six months.

He returned to Kimberley where his health improved. From age 40 his

heart condition returned with increasing severity until his death from

heart failure in 1902, aged 48, at his seaside cottage in Muizenberg.

The Government arranged an epic journey by train from the Cape to

Rhodesia, with the funeral train stopping at every station to allow

mourners to pay their respects. He was finally laid to rest at World's

View, a hilltop located approximately 35 kilometres (22 mi) south of

Bulawayo, in what was then Rhodesia. Today, his grave site is part of

Matobo National Park, Zimbabwe.

The continued presence of Rhodes's grave in the Matopos hills has not

been without controversy in contemporary Zimbabwe. In December 2010 Cain

Mathema, the governor of Bulawayo, branded the grave outside the

country's second city of Bulawayo an "insult to the African ancestors"

and said he believed its presence had brought bad luck and poor weather

to the region. The grave site is considered an important national and

historic monument on protected land which attracts many tourist visitors

every year.

In February 2012, Mugabe loyalists and ZANU-PF activists visited the

grave site demanding permission from the local chief to exhume Rhodes's

remains and return them to Britain. This was considered a nationalist

political stunt in the run up to an election, rather than representing

any genuine national desire to remove the grave. Local Chief Masuku and

Godfrey Mahachi, one of the country's foremost archaeologists, strongly

expressed their opposition to the grave being removed due to its

historical significance to Zimbabwe. Then-president Robert Mugabe also

opposed the move.

In 2004, he was voted 56th in the SABC 3 television series Great South

Africans.

At his death he was considered one of the wealthiest men in the world.

In his first will, written in 1877 before he had accumulated his wealth,

Rhodes wanted to create a secret society that would bring the whole

world under British rule. The exact wording from this will is:

To and for the establishment, promotion and development of a Secret

Society, the true aim and object whereof shall be for the extension of

British rule throughout the world, the perfecting of a system of

emigration from the United Kingdom, and of colonisation by British

subjects of all lands where the means of livelihood are attainable by

energy, labour and enterprise, and especially the occupation by British

settlers of the entire Continent of Africa, the Holy Land, the Valley of

the Euphrates, the Islands of Cyprus and Candia, the whole of South

America, the Islands of the Pacific not heretofore possessed by Great

Britain, the whole of the Malay Archipelago, the seaboard of China and

Japan, the ultimate recovery of the United States of America as an

integral part of the British Empire, the inauguration of a system of

Colonial representation in the Imperial Parliament which may tend to

weld together the disjointed members of the Empire and, finally, the

foundation of so great a Power as to render wars impossible, and promote

the best interests of humanity.

Rhodes's final will left a large area of land on the slopes of Table

Mountain to the South African nation. Part of this estate became the

upper campus of the University of Cape Town, another part became the

Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden, while much was spared from

development and is now an important conservation area.

Rhodes Scholarship

In his last will and testament, he provided for the establishment of the

Rhodes Scholarship, the world's first international study programme. The

scholarship enabled students from territories under British rule or

formerly under British rule and from Germany to study at Rhodes's alma

mater, the University of Oxford. Rhodes' aims were to promote leadership

marked by public spirit and good character, and to "render war

impossible" by promoting friendship between the great powers.

Memorials

Rhodes Memorial stands on Rhodes's favourite spot on the slopes of

Devil's Peak, Cape Town, with a view looking north and east towards the

Cape to Cairo route. From 1910 to 1984 Rhodes's house in Cape Town,

Groote Schuur, was the official Cape residence of the Prime Ministers of

South Africa and continued as a presidential residence of P. W. Botha

and F. W. De Klerk.

His birthplace was established in 1938 as the Rhodes Memorial Museum,

now known as Bishops Stortford Museum. The cottage in Muizenberg where

he died is a provincial heritage site in the Western Cape Province of

South Africa. The cottage today is operated as a museum by the

Muizenberg Historical Conservation Society, and is open to the public. A

broad display of Rhodes material can be seen, including the original De

Beers board room table around which diamonds worth billions of dollars

were traded.

Rhodes University College, now Rhodes University, in Grahamstown, was

established in his name by his trustees and founded by Act of Parliament

on 31 May 1904.

The residents of Kimberley elected to build a memorial in Rhodes's

honour in their city, which was unveiled in 1907. The 72-ton bronze

statue depicts Rhodes on his horse, looking north with map in hand, and

dressed as he was when met the Ndebele after their rebellion.